Towards a Green Thomism:

Ah! If we could and would only listen to the lesson of the bees…how much better the world would be! Working like bees with order and peace we would learn to enjoy and have others enjoy the fruit of our labors, the honey and the wax, the sweetness and the light of this life here below.

Henry David Thoreau, you suspect? Peter, Paul and Mary? A poster at the local organic co-op lamenting the impact of some colony collapse disorder? Not quite.

These words come from a 1947 papal address that Pope Pius XII gave to a gathering of Italian apiarists. He exhorted them to continue in their work of raising bees, which “by its nature and significance has a psychological, moral, social and even religious interest of no small value.” After all, he continued, “what lessons do not bees give to men who are, or should be, guided by reason, the living reflection of the divine intellect!” In this simple address to a gathering of Italian bee-keepers, I am struck by the confidence and tenderness with which the Holy Father exhorts them in their labor, recognizing that in their working so closely with nature and natural creatures, they are being offered something of a tutorial in the Christian life.

Those of us with a more modern attitude toward the created order might find in his address a romantic, even quaint, zeal for the simpler life that more sophisticated Catholics ought to politely (and politically) dismiss. Such rhetoric, we might suggest these days, is best left for the “tree huggers,” the “granola types,” as well as their “lefty” friends. After all, don’t thoughtful Catholics know better than to embrace the fads of such environmental sentiments?

But such a dismissal of all things “green” would be a mistake, and ultimately inconsistent with some of our most fundamental Catholic convictions. Indeed, among all of the Christian communities, and among all religions ever, Catholicism is best equipped to enter into the conversations about environmental stewardship; to hold at arm’s length what appears to be a “liberal thing” would betray a fundamental ignorance of our own tradition, and may perhaps lead to tragically missing opportunities for evangelization.

To be sure, there are currents in the broad stream of the environmental movement that Catholics must reject and work to overcome. But this essay is ordered toward a reconsideration of too-casual a dismissal, and invites those who take Catholicism seriously to discern in the groundswell of environmental “awareness” an opportunity for evangelization. In his 2010 World Day of Peace Message, Pope Benedict XVI made an urgent appeal for a fundamental renewal of our thinking on the comprehensive question concerning the stewardship of creation. Far from calling for staunch opposition, the Holy Father asked us to engage the issues seriously. “Humanity needs a profound cultural renewal,” he asserted. “It needs to rediscover those values which can serve as the solid basis for a brighter future for all.”

1

The rise of today’s environmental movement is for us faithful Catholics precisely that opportunity to rediscover those values. What needs to be rediscovered is a robust “philosophy of nature,” one that recognizes the intelligibility of creatures, their individual integrity and their ordered relationships within a cosmic whole, as well as a vision of the material order in which creatures enjoy a kind of deference of respect. Most importantly, we need to rediscover a conception of the human person as the supreme member of that visible order and as the one who is therefore uniquely poised to occupy the place of steward; an ethics of use which is able to respect both the integrity of natural things and the supernatural vocation of the human person.

This is not the first time the Church has been called upon to correct a widely held but alien vision of material creation and our place within it. The Albigensian heresy of the twelfth century (itself an ancestor of a still earlier heresy—Manichaeism, which St. Augustine espoused for nine years) was, among other things, an environmental philosophy that endorsed a vision of material creation as utterly corrupted and the human person as an abomination in a disordered creation. The Order of Preachers, which came to be through the vision of St. Dominic, was inspired to combat such a faulty theology of creation. Among others, Thomas Aquinas answered the call to serve. His unparalleled genius and personal holiness was enough to inspire others in their search. But perhaps more importantly for today’s purposes, he proposed a vision of the created order that can supply us with the necessary tools to address the meaning of the environment and our place within it. Of course, even as an ardent Thomist, I know it is not enough simply to repeat the insights of the thirteenth-century mendicant. But we would be very well served if we would renew our efforts to consider how Thomism can address some of the fundamental questions surrounding environmental stewardship.

There are many challenges ahead for anyone seeking to inaugurate (what we might call) a “Green Thomism,” not the least of which is terminology. Thomas developed a theology of creation which has provided the parameters for the theological tradition for centuries, and yet here we are speaking of “environmental” awareness. While both approaches seek to address the meaning and significance of material creation, there are important differences in nuance, differences we cannot overlook in any attempt to bring the Thomistic doctrine of creation into conversation with emerging environmental awareness.

In fact, to speak of “creation” and to speak of the “environment” is to speak in two distinct ways; the reference points are not the same. To put it simply: as far as the Catholic (

read, Thomistic) theological tradition is concerned, the human person does not live merely in an environment, does not simply take up space. Rather, the human person dwells in a world—a created cosmos. And to conflate the two orders, the order of creation with the order of the environment, distorts the issues. Learning to appreciate the significance of a doctrine of creation, as opposed to developing a mere environmental “sensitivity,” provides both the necessary foundation for an appropriation of the tradition as well as a sufficient warning for all those who are rightly interested in the obligations of stewardship.

In an essay entitled “The Philosophical Act,” the German Thomist Josef Pieper (1904-97) argues that there is a difference in meaning when we speak of something in a “location,” something in an “environment,” and something in a “world.”

2 What differentiates proper usage, Pieper argues, is not a consideration of the object’s ambient circumstances; rather, it is the distinct capacities of the object in question. Thus, we speak of the “location” of rock, the “location” of shale, or the “location” of oil, because rocks, shale, and oil are rather simple in their operations, their activities. But when it comes to plants and animals, we speak not only of their location but of their environment, because plants and brute animals do not merely occupy a position; they inhabit a place and interact with the elements surrounding them, drawing their ambient resources into their more complex operations.

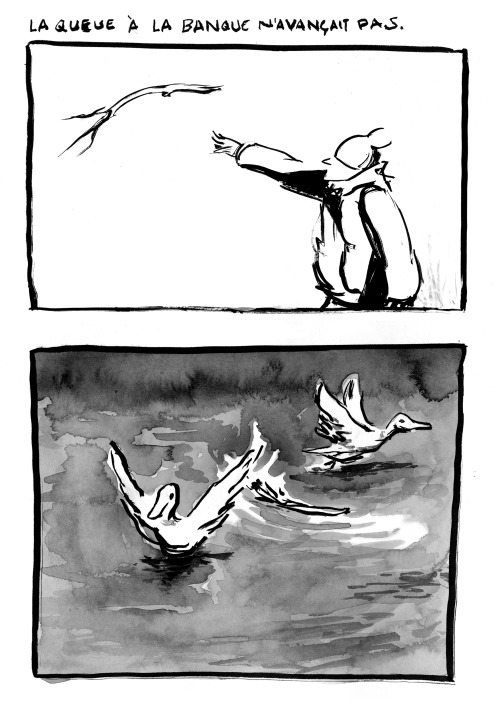

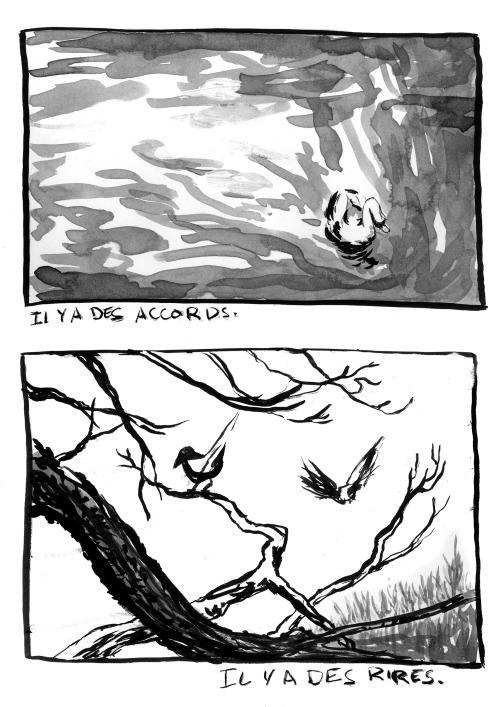

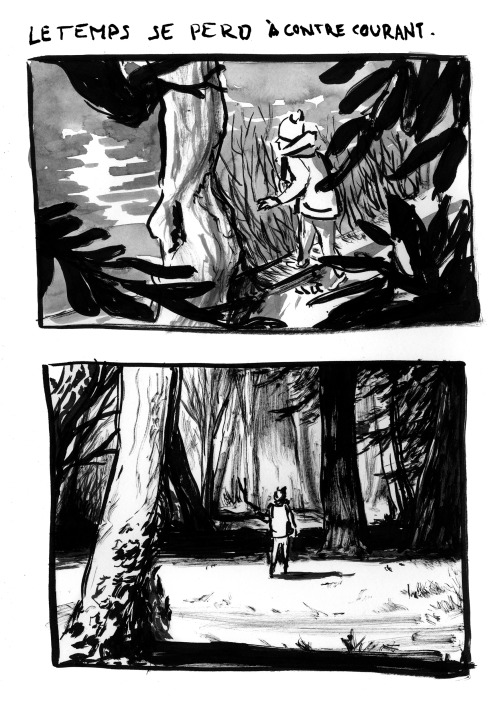

Yet there is only one kind of creature, Pieper argues, who occupies a world, a cosmos: the human person. The human person, with his or her capacity for intellectual comprehension and understanding, occupies neither merely a location nor merely an environment, but something much, much more. It is this unique spiritual capacity that renders all conversations about “humans and their environment” inadequate. An appeal to ordinary experience confirms this point: there, at the top of a beautiful mountain range in the western slopes of Rocky Mountain National Park and amid the migrating elk and summer fauna, gather a species of animal every July to warm in the sun and bask in the surroundings—the human person! Humanity is the only species equipped not merely to occupy that mountain range, but to wonder at its majesty, to contemplate its splendor, to prescind from the mere task of survival and survey the beauty of it all. A creature both corporeal and spiritual, he enjoys not only the beautiful location, but the cosmos of which he is a part; he not only sees the world, but beholds the world, and in so doing expresses the vocation of man as steward and, ultimately, as the only image and likeness of God (cf. Gn 1:26) on earth.

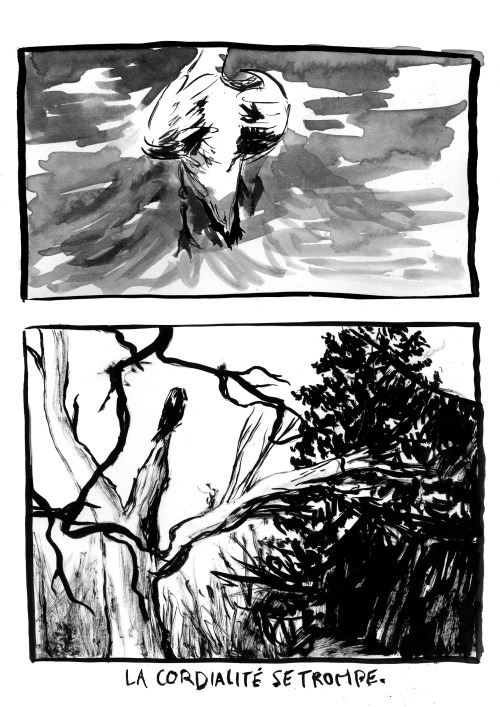

This often transitory experience of awe before the beauty of the created order is a glimpse into our origins. It is an intuition into our status as creatures within a cosmos, created and continually drawn by the God who is love. What is more, the experience of awe is not simply an insight into creation as such, as an object of wonder or consideration; rather, it is a privileged insight into our relationship with God and creation prior to the fall. Awe is a glimpse into that naturally gifted state in which the alienation between lower creation and man has not yet been fractured. Indeed, just as couples in their chaste, married love capture a glimpse of the pre-fallen innocence among the sexes (as John Paul II has suggested in the development of his “theology of the body”),

3 so too, the experience of awe—that kind of ecstasy experienced through the beauty of the created order and its goodness that so often accompanies our encounters with nature—can be understood as an intuition of that pre-fallen condition in which the alienation between the human person and creation did not exist.

For this reason, the Church should not be indifferent to preserving that same encounter. Today so many men and women are rediscovering the beauty as well as the fragility of the natural order (e.g., attention to our natural resources, greater regard for healthy lifestyles and regular exercise, concern over recycling and sustainability, more awareness regarding the growing and transporting of foods as evidenced in the “fair trade,” “slow food,” and “organic” movements, seeking healthier and more equitably purchased food, etc.). These natural discoveries can become precisely the first tutor in the Christian faith, as nature becomes the first “place” where one discerns God’s presence, the place where God first reveals himself in one’s experience and imagination. As Pieper suggests, “the first wonder one feels forms the first step on the path that leads to the beatific vision, the state of blessedness resulting from reaching the Ultimate Cause. But that human nature is designed for nothing less than such an end is proved by the ability of the human being to experience the wonder of creation.”

4

For example, one might begin to appreciate the value of a wildlife “sanctuary,” not merely as that space which protects a valued species and its habitat, but precisely as that space in which the human person, as a creature whom God has willed for himself (cf.,

Gaudium et Spes, no. 24), might begin an apprenticeship in his or her sacred vocation. By entering into that moment of receptive contemplation, by affirming the goodness of the species and their respective habitats, we prescind from the more typical understanding of dominion over creation as a divinely-sanctioned imperative to do something, and enter into the prior and deeper activity of beholding. By intentionally beholding the goodness of creation, we share in the life of God who first beheld all things as very good.

Catholics should therefore not be indifferent to the created order. We ought to strive to preserve the experience of nature as a privileged occasion of divine encounter and to understand that the obligation we have to protect such spaces is precisely rooted in our larger vision of life as more than a species inhabiting an environment, but as members of the body of Christ—Christ the Logos of the Creator, Christ the Logos of creation.

Evangelizing the environmentalists: From conservation to consecration

One essential task in the evangelization of the environmental movement will be the untiring affirmation of the spiritual destiny of the human person, a creature in the environment, but not of the environment—a person made for eternal union with the Triune God and for much more than what most of the rhetoric of environmentalism today offers. There is no need for the Green Movement to be taken over by “the left.” This is instead fertile ground for the Christian message: the human person is not a mere creature among creatures, whose destiny is inscribed within the passing eons of matter following upon matter. Rather, the good news of Jesus Christ invites us to beatitude, to an eternal friendship that outpaces the order of material creation as we have come to know it, to a glorified state of dwelling within a kingdom beyond our comprehension.

And yet, at the same time, we cannot allow the eschatological rhetoric to dominate the very real obligations we have to each other and to the world which are incumbent upon us as

viatores, as a people still on the way. The supernatural destiny of the human person alive in Christ is a mystery of joy that goes beyond our comprehension and continually invites us to a constant witness with our lives. At the same time this witness to our supernatural destiny cannot evacuate our natural lives of theological significance; to do so would be simply to replace the materialist distortions of the worst of the environmental movement with an excessively spiritualist rhetoric of a vapid Catholicism. The event of Jesus Christ calls us to something deeper. In taking on our human nature, our flesh, he takes on all that goes with such fleshly existence—time, history, culture—as well as the body and all that goes with embodiment: location, place, region, soil, flora and fauna. Our fleshly existence is no longer merely the occasional location where God’s grace happens to interact; rather, our fleshly existence becomes the medium through which the renewal of all things takes place. As Tertullian (c. 160-c. 220) said centuries ago,

caro cards salutes—the flesh is the hinge of our salvation.

5

In the mystery of the most Holy Eucharist, where the Lord continues to offer himself in Body and Blood for us and for our salvation, we too, now members of that one body, offer ourselves united with him in the one sacrifice of praise. In offering ourselves, we offer all that goes with being ourselves as well—our work, our families, our property, our prosperity—all that is touched by human hands and is the fruit of human labor now is offered in the sacrifice of the Mass. As St. John Paul II so beautifully reminisced in

Ecclesia de Eucharistia: “I have been able to celebrate Holy Mass in chapels built along mountain paths, on lakeshore and seacoasts; I have celebrated it on altars built in stadiums and in city squares … This varied scenario of celebrations of the Eucharist has given me a powerful experience of its universal and, so to speak, cosmic character. Yes, cosmic! Because even when it is celebrated on the humble altar of a country church, the Eucharist is always in some way celebrated

on the altar of the world. It unites heaven and earth. It embraces and permeates all creation.”

6 Our care for the environment is made complete because all things are returned to their creator. The original command to “till and keep the earth” (Gn 2:15) is now fulfilled in the new command of the Eucharistic sacrifice. Our mission is therefore not merely the

conservation of the earth’s resources, but the

consecration of the earth’s resources. No longer stewards of the earth, but sons and daughters of God in Christ, we return all things to the Father, through whom all good things come.

St. Thomas and the rediscovery of reality

To reorient others toward reality, we Catholics must address more robustly the material conditions of being human, developing a theology of embodiment—and all that goes with embodiment, not merely a theology of the body.

7 In order to develop a sound vision of our relationship within the created order—the environment, if one insists—we will need to reaffirm the ontological priority of that same order which is the human being’s necessary habitat. For no human being, not even one capable of contemplating an intelligible cosmos, does so in a vacuum. Rather, the native habitat of the human person as an embodied, intellectual creature is a material cosmos of created natures, the ontological density of which prepares the person for an engagement with Being. St. Thomas insists that, notwithstanding the dignity of the human being as the image of God (

imago Dei), the human person nonetheless occupies the lowest order of intellectual creatures because the human being is utterly dependent upon a material substance in order to engage in any intellectual acts. This is one of the central claims of Thomas’ philosophical and theological realism, and it provides one of the most vital links to any effort to engage in the rise of environmental awareness.

At the heart of a sound environmental ethic consonant with Catholic tradition lies a natural philosophy of being that provides, among other things, a robust vision of an order of intelligible creatures (utterly dependent upon a provident First Cause) whose causality extends to the operations of individuals—their formal intelligibility, as well as their purpose or finality.

8 In order to cast the human person properly as an intellectual creature inhabiting a material cosmos, we will need a realist philosophy of the natural order as the necessary complement of the human person. In such a realist world, the order of causality is understood to inhere in things (as opposed to the Enlightenment reversal in which now all “meaning” inheres in the individual thinker; now you have your “meaning” and I have mine, you have your “truth” and I have mine). The formal intelligibility of living organisms as well as the finalities toward which they naturally tend are objectively constituted in reality. As any good Thomist knows: “The first act of the intellect is to know, not its own action, not the ego, not phenomena, but objective and intelligible being.”

9 Creation calls the human seeker

out of himself,

into a world of relationship and—we pray, preach and work—

up to the Creator.

Once again, we can understand the increasing emergence of environmental awareness as the un-thematic revolt of conscience among those descendants of the Enlightenment who intuit that something is deeply flawed in our approaches to the natural order and that our habits of treating nature as a mere raw datum of purposeless matter is erroneous. Green Thomism can contribute to the renewal of an eco-realism by supplying not only a richer notion of the person as the subject who stewards, but also a richer notion of created things as objects to be stewarded.

10

While it can often be frustrating to engage in a dialogue with a movement that is as diffuse as “environmentalism,” especially with all its left-leaning political baggage in tow, Catholics would do well to take up the challenge and see in this

sensus populi an opportunity for the

sensus fidelium: to see what is moving the human heart, to understand what is important to our neighbors, and then to show them how that can be even more true, more beautiful, more enduring

in Christ. For to do so would be to take up the invitation of Pius XII, to mimic the bees in their constant search for sweetness and delight wherever it is found:

Let them learn therefore to enter with respect, trust and charity into the minds and hearts of their fellow-men discreetly but deeply; then they like bees will know how to discover in the humblest souls the perfume of nobility and of eminent virtue, sometimes unknown even to those who possess it. They will learn to discern in the depths of the most obtuse intelligence, of the most uneducated persons, in the depths even of the minds of their enemies, at least some trace of healthy judgment, some glimmer of truth and goodness.

11

In the tradition of St. Thomas, grace presupposes and must hence build upon nature. As the popular mind is taken more and more by the conversation and preservation of the natural, the Church finds therein unique opportunities to “take every thought captive” (2 Cor 10:5) and so help environmentalists see how nature exists ultimately to point us to the supernatural. Pius XII of course knew bees would teach us only so much, get us only so far, but teach us they can. Just as the great teacher, Jesus Christ, relied on the birds of the air and the flowers of the field to speak to us of the Father’s loving care, we cannot allow today’s ecological movements to be co-opted further by atheism, the New Age, radical feminism and other anti-Catholic causes. The earth and all that is in it belong to the Lord, and we Catholics must teach the nations that to gaze upon and to protect the natural order is actually a call to become a steward and an image of God alone.

Originally published in

Homiletic and Pastoral Review.

The post

Towards a Green Thomism appeared first on

The Distributist Review.