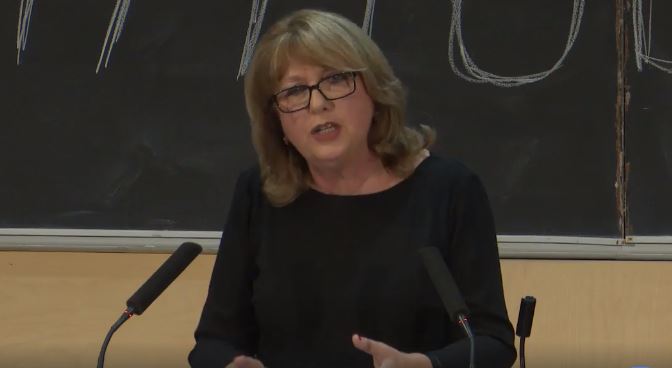

Former President and newly elected Chancellor of Trinity College Dublin, Mary McAleese, has trained her sights once again on infant baptism and the consequent rights and obligations of Christian parents to raise their baptised children as Christians. She did so while delivering the annual Edmund Burke lecture in Trinity the other night.

Dr McAleese advances a model of child autonomy that would curtail these rights and obligations and ‘free’ the child at an earlier age to accept or reject the religion of their family.

Crucially, what she doesn’t make clear is at what age a child should gain this right, and what should happen if the parents don’t accede to their child’s demands. Should the State intervene when the child is say 14, and no longer wants to attend religious service? If that is so, then she wants to make the State very powerful indeed. This would have Edmund Burke turning in his grave as he was hugely critical of the way the French Revolution made the State all-powerful in its drive to enforce its vision of society.

In her talk, Dr McAleese drew heavily on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). She said that parents in the past “had the right to baptise, raise and educate their children according to their own faith, convictions and rituals but now [under the CRC] they had an obligation to do so in a manner which respected and facilitated the child’s right to form its own independent and different views when capable of doing so … for their children are and must be free to choose for themselves when capable of doing so.”

She said that the Catholic Church (for some bizarre reasons she calls it the Latin Catholic Church) is refusing to undertake a review of its canon law and to be in full compliance with the CRC.

Dr McAleese claimed that she has no problem with infant baptism per se but she has issues with its consequences under Church (canon) law. Some of those consequences, she asserts, “are not consistent with the child’s right to freedom of conscience, thought and religion including the right to change religion. These rights are understood today differently and that changed understanding has yet to be reflected in canon law.” Unfortunately, she does elaborate on this last point so we don’t really know how canon law should be made more ‘respectful’ of children’s rights.

She focuses on the fact that canon law includes “the imposition of lifelong membership which can never be rescinded”. She compared baptism to a contract, saying that onerous contractual obligations might be rendered to be voidable by the child when he has the maturity to do so, with full knowledge and consent, while the Church offers no such option to adults or to children.

But we all know people who have left the Church, even at a young age, embracing another faith or no faith at all. They didn’t breach any contract and they have no obligations towards their former Church. This happens every day with no legal consequences of any sort.

Dr

McAleese correctly states that canon law has a complex system of

tribunals,

trials, penalties and, in theory, even children between the age

of 16 and 18 can

be imposed some form of mitigated penalties. But, seriously, how

many children does

she know in Ireland that have been tried and found guilty of

schism, heresy or

apostasy?

Canonical

trials generally only take place when the person has a specific

public role in

the Church. For instance, if someone is a priest, or lectures in

theology, and publicly

repudiates the Catholic faith.

It

is not clear if McAleese is expecting canon law to facilitate

the process of apostasy

for children, maybe through some formal recognition, which would

be an absurd

demand. But, in any case, the Church has no means to stop

someone from leaving and

it would be against its teaching to force anyone not to follow

their

conscience.

Mary

McAleese's attack is problematic in many respects. Firstly, one

wonders if this

constant criticism of the religious beliefs of a large part of

the Irish population

fits appropriately with the dignity and the responsibility of a

former president

of Ireland.

Moreover,

her attack to Catholics can be easily extended to other

religious faiths, as

all of them educate their children according to beliefs of the

parents. Is teaching

the Koran and expecting young believers to follow the tenets of

Islam a breach

of the human rights of young Muslims?

Unless she is targeting

only

Catholics, what she writes about baptism and catechesis is true

also for any

other form of cultural initiation and education of children,

including non-religious education.

Nonetheless, she presses on and states: “When canon law says an infant can be held to the fiction of [baptismal] promises it did not make and never had an opportunity to evaluate, validate or repudiate when capable of doing so, human rights law says ‘no’ it cannot. The current extensive catechesis of obligation whether at home or school or church is problematic as a result”.

Children do not choose to be baptised, of course, but what else do they choose at the beginning of their lives? Nothing significant. Later, as they become more mature, it is the role of their parents to make them more responsible and to involve them in decisions.

Claiming that canon law is ‘imposed’ on them is not different from saying that language, or citizenship, or legislation, or any other expression of a particular culture, are inevitably ‘imposed’ on them because of the choices made by their parents or their community. One day they will be able to reject or accept those choices but how this is a breach of human rights it is a mystery, and it is even more mysterious what Mary McAleese proposes as an alternative, other than giving the State far more powerful to interfere in the lives of religious families and communities.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento