In Ireland in the past, unmarried mothers and their children were harshly treated as a result of a potent brew of Victorian values and a strict application of Catholic morality. But as we will see, in other countries such as Britain and Sweden, the ‘science’ of eugenics was often applied instead, with fearsome results.

This emerges, for instance, when we consider the debate around the Mental Deficiency Act that in 1913 created the legal categories of “feeble-minded person” and “moral imbecile” in the UK. Those categories related more to the ability to behave according to social expectations, particularly with regard to sexuality, than to abnormal psychological traits. This law was not repealed until 1959.

Alfred Frank Tredgold was the most influential ‘mental deficiency’ specialist of the time. A leading member of the Eugenics Society, he wrote the ‘Text-book of Mental Deficiency (Amentia)’, the “generally accepted standard work”, according to the British Medical Journal.

In this book Tredgold presents a number of working-class young women as case studies for the diagnosis of mental deficiency. This diagnosis is clearly related, in most of the case studies, to sex and pregnancy outside marriage.

Under the Mental Deficiency Act, thousands of young women who had children outside marriage were incarcerated or put in institutions because of fears that they would otherwise become pregnant again.

As Carolyn Oldfield explains in her PhD thesis entitled, ‘Growing up Good? Medical, Social Hygiene and Youth Work Perspectives on Young Women, 1918-1939’: “While this incarceration could extend throughout women’s fertile years and after, authorities directed their efforts towards identifying and segregating adolescent and young adult women, in order to prevent what was expected to be a cycle of repeated pregnancies and short-term recourse to the workhouse”.

Josiah Wedgwood, the main opponent of the Act in the British Parliament, maintained that the legislation purposely targeted women who went into workhouses to have children. (The workhouses were often the alternative to mother and baby homes in Britain as well as Ireland).

Outside the Parliament, one of the few opponents was G. K. Chesterton, who also fought eugenics (human selection) throughout his life. He seized on the subjectivity and almost infinite elasticity of terms like ‘defective’ or ‘lunacy’.

He called the Bill “a scheme to impose all the segregation, ‘control,’ and loss of citizenship which are the tragic consequences of lunacy on a very large class of people who are not lunatics. … the new Bill will enable officials to treat as defective infants a vast and vague multitude of grown-up people who have suffered from any one of a million unnamed accidents of daily life; a number not only indefinite but infinite. They can be seized upon any excuse or none.”

In early twentieth century, proponents of eugenics were particularly focused in identifying the “defectives” as they believed that mental deficiency could be passed from one generation to another, and consequently deteriorate the quality of the overall population.

In the UK, the eugenicists failed to secure the sterilisation of mental defectives – which Winston Churchill had advocated – due to the opposition coming from sectors of the medical profession, the Catholic Church, and the labour movement.

They succeeded instead in the Nordic countries, particularly in Sweden, and in some American states. About 170,000 forced sterilisations were performed between the 1920s and the late 1970s in Scandinavian countries. For this purpose, the Swedish Institute for Racial Biology was set up at Uppsala University in 1922. Together with sterilisation, the Nordic governments enacted marriage limitation, castration and abortion laws.

Cambridge historian Professor Véronique Mottier writes that among the victims of these policies were “socially deviant groups such as unmarried mothers”.

Tellingly, she says that while “feminists were to be found on both sides of the debate – supporting and opposing eugenics – most opposition came from liberals, who rejected state intervention in private life, and Churches, particularly the Catholic Church.”

She points out: “Social democrat reformers were amongst the pioneers of eugenic ‘science’ as well as policy practices in Europe. A number of eugenic policies such as forced sterilisation of ‘degenerates’ were strongly promoted by the Left and were first applied in countries such as Switzerland and Sweden.”

Eugenic policies also included “education programmes, non-voluntary incarceration in psychiatric clinics, removal of children from parental homes, prohibition to marry, as well as measures that specifically targeted vagrants, ‘gypsies’, and, more generally, socially deviant groups such as unmarried mothers, ‘sexual deviants’, or people with physical or mental impairments”, Prof. Mottier says.

In Canada, in 1928 the province of Alberta created a Eugenic Board that approved more than 5,000 procedures of involuntary sterilisations on people classified as “mentally deficient”, mostly women. This happened with the participation of leading scientists of the time.

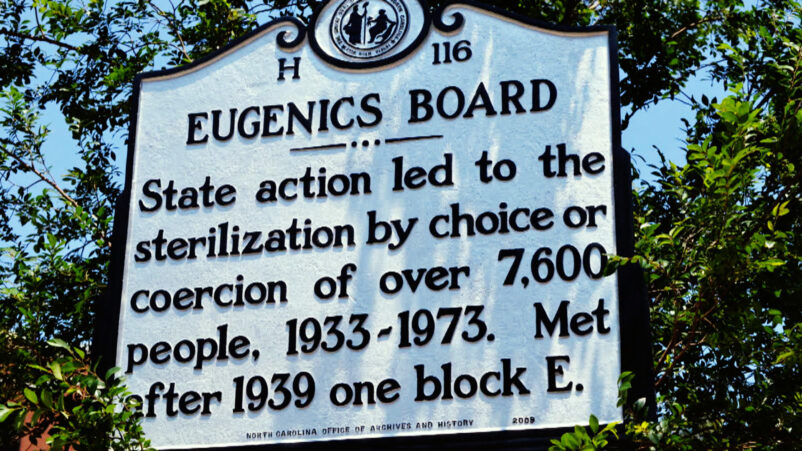

In the United States, compulsory sterilisation laws were adopted by over 30 states and affected more than 60,000 individuals who were mentally disabled or belonged to socially disadvantaged groups. (See here for a comprehensive account.)

The most famous of them was Carrie Buck, a teenager who became a test

case for Virginia’s new eugenics legislation, in 1924. Carrie was raped

by a member of her foster family, then declared feebleminded and

“probable potential parent of socially inadequate offspring”. The

request for her sterilization went up to the Supreme Court of the US.

Justice Oliver Holmes famously said that “three generations of imbeciles

are enough”, and Buck’s case opened the floodgates of eugenics and led

to involuntary sterilization of thousands of people.

As mentioned, sterilisation was never legislated for in the UK. Following the Mental Deficiency Act, detention in institutions was the chosen road.

Once a clear association between young women’s sexual activity and their identification as ‘mentally defective’ was established, they would be practically incarcerated without any trial or recourse to the adult penal system.

The marriage of pregnant ‘mentally defective’ girls was also discouraged because it would make them more likely to bring up their children themselves, rather than giving them for adoption. But also because the stability of marriage would encourage them to have more children and, in this way, to pass on them their “defective genes”.

The fact that those practices were common at the time does not justifies them. Nonetheless, the consideration of the broader international context helps us understanding that the institutionalisations of young unmarried mothers took place not only in Ireland and not only where the Catholic Church had influence.

We imagine that once religion was removed from the picture, unmarried mothers would be treated humanely but when ‘science’ was applied instead, we got eugenics and huge levels of cruelty.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento