IL REFERENDUM

L'Irlanda salva donna e famiglia: «Come Davide contro Golia»

L'inaspettata vittoria del No al referendum irlandese per togliere dalla Costituzione il diritto della donna a rimanere a casa per badare alla famiglia e l’unicità della famiglia naturale. La Bussola intervista Angelo Bottone, tra i promotori del comitato per il No. «È una cesura col decennio di riforme liberali».

Nelle intenzioni di Leo Eric Varadkar, il capo del Governo irlandese, avrebbe dovuto essere un modo di festeggiare alla grande l’8 marzo; in realtà è stata una sorta di anticipazione della Festa di San Patrizio, il Patrono d’Irlanda. Un referendum su due quesiti che, con esito positivo, avrebbero proseguito il drastico processo di laicizzazione dell’Irlanda in corso. Il primo quesito riguardava la definizione della famiglia che, come nella Costituzione italiana, è fondata sul matrimonio. La proposta referendaria, rigettata dal 67,7% dei votanti, intendeva definire la famiglia quale fondata su “matrimonio e relazioni durature”.

Questa espressione “relazioni durature”, al plurale, avrebbe compreso non solo quelle che sono state chiamate “relazioni orizzontali”, ossia fra adulti, come le convivenze, ma anche quelle “verticali” fra genitori single e i propri figli. Il problema principale è che a differenza del matrimonio che deve essere consensuale, pubblico, registrato, ecc., lo Stato non sa chi è in queste “relazioni durature”, non si sa quando cominciano o finiscono perché l’anagrafe non registra le convivenze.

Paradossalmente, l’inclusione di queste “relazioni durature” nella definizione costituzionale di famiglia, avrebbe conferito un riconoscimento legale obbligatorio anche a chi, per esplicita volontà, non lo desiderava.

Il secondo quesito è un po’ più complesso. La formulazione attuale riconosce il valore della vita domestica della donna per il bene comune e dice che lo Stato deve far sì che “le madri non siano obbligate a lavorare fuori casa da necessità economiche, negando così i loro doveri a casa”. Il linguaggio può apparire antiquato. Alcuni si lamentano perché rispecchia la mentalità del 1937, quando la Costituzione irlandese fu scritta ma, nel tempo, i giudici hanno interpretato l’articolo in riferimento non solo alle madri ma anche ai padri.

Questo articolo giustifica l’assistenza pubblica nei confronti di chi lavora in casa e, a differenza di quanto hanno scritto anche alcuni giornali italiani, non obbliga nessuna donna a rimanere a casa. La proposta referendaria, respinta dal 74,4% dei votanti, avrebbe sostituito l’articolo attuale con una formulazione completamente nuova, basata sul riconoscimento per il bene comune della cura che i membri della famiglia hanno reciprocamente. Questa proposta è stata criticata da quanti, seppur non contenti della formulazione originaria, hanno ritenuto la nuova come troppo debole. Alcune organizzazioni a difesa dei disabili, ad esempio, hanno sostenuto che così lo Stato avrebbe relegato la cura alla famiglia, invece di farsene carico.

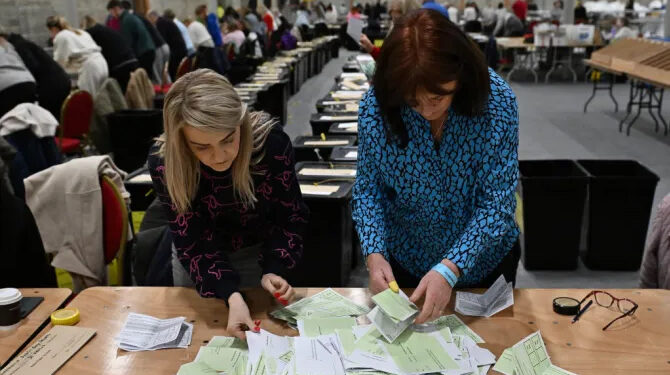

L’esito del Referendum è stato quello - assolutamente inatteso e sorprendente - di una schiacciante vittoria dei no. Un esito quasi choccante, anche a livello internazionale.

La Bussola ha intervistato uno dei più significativi intellettuali cattolici irlandesi – anche se con evidenti origini italiane - Angelo Bottone, docente di filosofia e ricercatore presso l’Iona Institute, un think tank pro-life e pro-famiglia che ha avuto un ruolo di primo piano nella campagna per il No. Il prof. Bottone è anche il presidente di Family Solidarity, un’associazione di famiglie cattoliche, anch’essa impegnata nella campagna referendaria. Family Solidarity è membro della FAFCE, la federazione europea delle organizzazioni familiari cattoliche.

Professor Bottone, l'esito del Referendum ha sorpreso molti osservatori. Voi organizzatori ve lo aspettavate?

Sinceramente, no. Domenica scorsa i sondaggi davano il No al 25% e gli indecisi al 35%. L’unica cosa che ci faceva sperare era il veder crescere il supporto per le nostre posizioni fra i cittadini più informati. Si percepiva un movimento nella direzione giusta ma i giorni erano ormai contati. Gli ultimi dibattiti hanno convinto gli indecisi ed il risultato è stato eccezionale. La percentuale di No nel secondo quesito (74,4%) è la più alta mai registrata nella storia dei referendum, mentre il primo quesito ha ricevuto la terza percentuale (67,7%) più alta. Come dire, mai come questa volta il popolo si è espresso così chiaramente.

Avevate contro tutti, come sempre: la grande stampa, e pressoché tutti i partiti ad eccezione di Aontù, la piccola formazione che si è staccata dallo Sinn Fein proprio a motivo della laicizzazione radicale della storica formazione nazionalista.

Vero, e questo rende il risultato ancora più significativo. Tutti i partiti, di governo e di opposizione, appoggiavano entrambi i referendum. Aontù, l’unico partito contrario, ha solo un rappresentante eletto in parlamento e, a differenza degli altri, non riceve finanziamenti pubblici perché non ha superato la soglia necessaria. È stata veramente la battaglia di Davide contro Golia. Tanto più che la campagna per i Sì è stata condotta da diverse organizzazioni no-profit fortemente finanziate dallo Stato mentre dalla nostra parte c’erano piccoli gruppi di ispirazione cristiana e alcuni senatori indipendenti, tutti animati da buona volontà ma con scarse risorse.

C’è da notare anche la partecipazione nella campagna per il No di alcune organizzazioni di femministe radicali, che su altri temi ci vedono contrapposti. Queste femministe si sono opposte particolarmente al secondo quesito, che avrebbe rimosso la parola “madre” e “donna” dalla Costituzione. Le femministe radicali, da sempre contro l’ideologia gender, hanno interpretato questo come un tentativo di neutralizzare i riferimenti espliciti alla donna nella carta costituzionale.

Il governo aveva scelto proprio la giornata mondiale della donna come data simbolica, nel tentativo di far passare i due quesiti più facilmente, ed invece è successo il contrario. L'otto marzo sarà ricordato come il giorno in cui gli irlandesi non hanno cancellato la donna dalla loro Costituzione. Tra le organizzazioni religiose, solo la Chiesa cattolica e quella presbiteriana si sono battute in difesa della famiglia: anglicani, mussulmani ed ebrei non pervenuti. Forse in nome del politically correct?

I vescovi cattolici hanno scritto una bella lettera, spiegando le conseguenze delle due proposte. I presbiteriani sono stati gli unici, tra le denominazioni protestanti, ad opporsi pubblicamente mentre non c’è stata alcuna indicazione di voto da parte delle organizzazioni islamiche ma, io direi, per un motivo preciso. Il primo quesito intendeva equiparare le “relazioni durature” al matrimonio e, in questo modo, avrebbe conferito un riconoscimento legale alle unioni poligame. Il matrimonio poligamo, accettato dai musulmani, sarebbe rimasto illegale perché la Costituzione prevede esplicitamente solo due coniugi. Tuttavia, non è illegale per un musulmano coniugato all’estero con più di una moglie venire a vivere con esse in Irlanda. Uno degli effetti dell’emendamento costituzionale sarebbe stata l’equiparazione delle famiglie poligamiche a quelle basate sul matrimonio. Non è una sorpresa quindi che i musulmani non si siano opposti.

Come avete fatto a convincere l'elettorato?

Non avendo molte risorse, ci siamo concentrati sui dibatti televisivi e radiofonici, piuttosto che su spot televisivi, manifesti o volantini. Un momento culmine è stato il dibattito in prima serata sulla televisione pubblica, martedì scorso. Maria Steen, anche lei dell’Iona Institute, è stata il volto del No. Madre di cinque figli, architetto ed avvocato. Una donna di fede, molto attiva nella campagna antiabortista del 2018. Il Sì era invece rappresentato dal vice-primo ministro e leader del partito di maggioranza Fianna Fail, Michael Martin. Un politico di primo piano, esperto, che bene rappresentava l’establishment. È difficile quantificare l’efficacia di questi dibattiti ma, visti i risultati, non c’è dubbio che il contributo di Maria Steen è stato vincente.

A proposito di partiti: questo voto è una solenne sberla alla diarchia Fianna Fail - Fine Gael, ma anche un segnale per lo Sinn Fein e gli altri partiti, che sono ben distanti dal Paese reale, non trova?

Si è trattato di un terremoto che ha riguardato l’intera classe politica. Il popolo è andato esattamente nella direzione opposta dei partiti. Non si è trattato solo di un voto antigovernativo, visto che i quesiti erano appoggiati anche dalle opposizioni. La distanza tra la realtà e la sua rappresentazione politica, o meglio, la mancanza di rappresentazione politica, non poteva essere più esplicita. È stato un voto totalmente antisistema, non previsto dai commentatori.

Si può guardare con ragionevole speranza al partito Aontù?

Al momento è ancora piccolo ma rappresenta l’unica alternativa al pensiero unico dominante. La campagna referendaria ha dato molta visibilità al loro leader, Peadar Tóibín e, visti i risultati straordinari, sono convinto che anche il partito ne trarrà qualche profitto.

Questo voto così netto e chiaro può essere letto come un freno che gli irlandesi hanno voluto mettere alla deriva scristianizzante degli ultimi anni?

Io sarei prudente nel trarre simili conclusioni. Il processo di scristianizzazione continua, ma il voto di venerdì rappresenta una cesura. È la fine di un decennio di riforme liberali che hanno comportato non solo la ridefinizione del matrimonio nel 2015, aprendo alle coppie omosessuali, e la legalizzazione dell’aborto nel 2018, ma tutta una serie di leggi e di decisioni politiche. Proprio in questi giorni una commissione parlamentare ha proposto la legalizzazione dell’eutanasia. Sembra che la classe politica irlandese, quasi a compensare un senso di inferiorità dovuta ad un passato troppo religioso, faccia di tutto per apparire la più anticristiana su temi sensibili. Il risultato dei referendum indica definitivamente un’altra direzione. Il popolo, almeno questa volta, ha detto no.

A partire dall'esito di questo referendum potrebbe iniziare una significativa ripresa, dopo anni difficilissimi, della presenza sociale e politica dei cattolici?

Non c’è una formazione politica di esplicita ispirazione cattolica. Ci sono politici, non molti, che non si vergognano della propria fede, e c’è ancora un sentimento religioso diffuso ma questo non si traduce in una proposta politica. Ieri sera, festeggiando, ci chiedevamo come capitalizzare questo successo. C'è molto da riflettere, ma per il momento lasciateci godere questa bellissima vittoria.