«Potrebbe immaginarsi che un giorno per mezzo di ingegnose invenzioni ogni singolo uomo, senza lasciare la sua abitazione, con un apparecchio possa continuamente esprimere le sue opinioni sulle questioni politiche e che tutte queste opinioni vengano automaticamente registrate da una centrale, dove occorre solo darne lettura. Ciò non sarebbe affatto una democrazia particolarmente intensa, ma una prova del fatto che Stato e pubblicità sarebbero totalmente privatizzati. Non vi sarebbe nessuna pubblica opinione, giacché l’opinione così [raccolta] di milioni di privati non dà nessuna pubblica opinione, il risultato è solo una somma di opinioni private. In questo modo non sorge nessuna volonté générale, ma solo la somma di tutte le volontà individuali, una volonté de tous»

giovedì, febbraio 25, 2021

martedì, febbraio 23, 2021

Ireland one of only two EU countries banning public worship

Ireland is currently one of only two countries in the whole of the European Union where the Government has put a complete stop to public worship. The other member-state is Slovenia. Restrictions on worship vary from country to country, from mild in Austria, to strict in Belgium.

In Belgium, dozens of Catholics gathered on Sunday in Brussels to protest the current rule that allows only 15 people to attend religious ceremonies. The protest took place in front of the Keokelberg national basilica, the fifth biggest church in the world that could contain more than 8,000 worshippers, with the purpose of showing the absurdity of some of the current regulations.

The protesters, together with members of other faith groups, are asking the Belgian Government to allow a number of participants in proportion to the size of the building, as it is the case in other countries. In the Netherlands, their neighbour, there is no limit in number. In France it is 30, while it is 50pc of the capacity in Italy.

Last year, Belgium had one of the strongest restrictions in Europe and public religious ceremonies were banned until the Jewish community appealed to the Council of State, which found the rules excessive. In December, the Government was obliged to ease the restrictions and it allowed 15 people per service, not including the celebrant and children under 12. The decision has left the larger faith communities unhappy and they are now hoping for further relaxation at a Government meeting on Friday.

Scotland’s ban has been attacked by father Tom White, Dean of the City East St Alphonsus Church in Glasgow, who has filed a pre-action letter with the Scottish government

“I speak for many in the church when I say that it’s very important to keep people safe and well during this pandemic,” the priest said. “But this can and should be done while also allowing people to fulfil their need to draw close to God and worship in community at the church. With appropriate safety measures, we can accommodate both of these outcomes, as is shown in England, Northern Ireland and Wales”, he said.

In other countries in Europe there are restrictions in terms of number of worshippers allowed to attend, or local and temporary bans, but no other state has prevented public religious celebrations for so long periods as in Ireland. This has happened for many months in 2020 and then, again, since January 2021.

Many voices have expressed criticism for the excessive measures.

Last November, businessman Declan Ganley sought leave to bring judicial review proceedings against the Minister for Health but the hearing of the case has been postponed several times now and when the ruling will eventually arrive it will be too late.

Meanwhile, a group of independent Protestant churches called 'Christian Voice Ireland' has launched a video “A Call to Reopen Churches in Ireland” featuring pastors and faithful. The group represents more than 80 Christian churches and ministries and they are asking for the Irish Government to reopen churches in Ireland with immediate effect.

Here is a list of what is happening in various EU countries, based on the official EU website Re-open EU.

Banned: Ireland and Slovenia.

No specific limits but worshippers must be socially distanced etc: Austria, Croatia, Finland, France, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia.

50pc of church capacity: Italy and Estonia.

20pc of church capacity: Latvia.

Max 500 participants depending on size of building: Denmark.

Max 50 participants: Iceland.

Max 15 participants: Belgium, Bulgaria.

Max 8 participants: Sweden.

Poland: one person per 15 m2.

Malta: one person per 4 m2.

Czechia: no more than 10pc of the venue’s seated capacity.

lunedì, febbraio 22, 2021

Vivo

Oggi è il mio compleanno e, cari amici, festeggiamo con una citazione del nostro amato Chesterton.

venerdì, febbraio 19, 2021

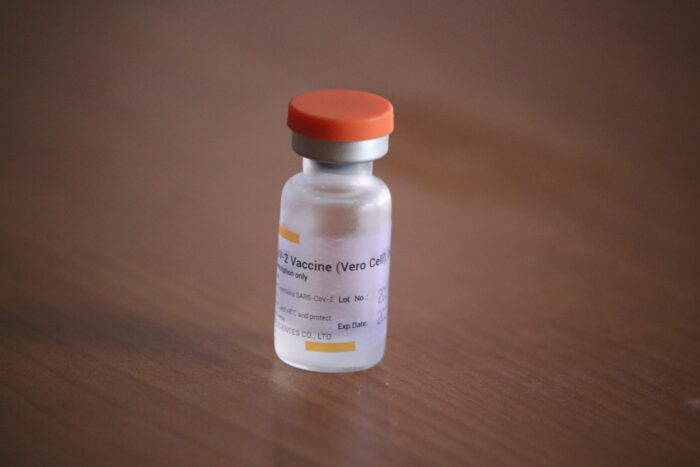

The immoral origins of certain cell-lines used in medical research

The use of vaccines that have some connection with abortion poses serious for the Christian conscience. In two other blogs (here and here) I have explained why it is morally permissible to avail of them if they are medically necessary and if there are no alternatives. Nonetheless, the problematic origin of those vaccines remains and has to be exposed.

As an example, I will concentrate on the HEK293 cell line because it is the one used to test, and sometimes to produce, some of the vaccines currently employed to fight Covid-19. I will also refer to another foetal cell-line called PER.C6, dating back to 1985, which at least one vaccine developer uses.

Cell lines are human cells cultivated in laboratories from a single source and they are utilised to discover and test drugs, to develop therapeutic regimes, etc. Many of them have very morally problematic origins.

Someone who is not familiar with this field will be surprised to discover how widely those kinds of cell lines are used in laboratory research.

For instance, H1 is the name of an embryonic stem line derived from the destruction of a spare human embryo initially created in a laboratory for IVF. H1 is the second most commonly used human embryonic cell stem line.

These cell-lines are now used so widely that is very likely those who work in the life sciences will, at some point of their career, encounter them. Not everyone has the same degree of responsibility with regard to their use in experiments or in treatments, but it should be said without ambiguity that it is always wrong to destroy human life at embryonic or foetal stage.

What is HEK293? HEK means human embryonic kidney while the number 293 refers to the sequence number of the experiment. (It does not mean that 293 babies were aborted to obtained it)

Doctor Alvin Wong has traced the origin of HEK293 and found that, while the original records are lost, we know that the kidney material comes from a healthy baby that was aborted in Leiden (Netherlands) around 1972. We know those details from Dr van de Eb, the professional who performed the abortion. He is the same scientist who created the PER.C6 cell line from human embryonic retinal cells, which are also used in vaccines.

This is how Dr van de Eb describes the origin of PER.C6: “So I isolated retina from a fetus, from a healthy fetus as far as could be seen, of eighteen weeks old. There was nothing special with the family history or the pregnancy was completely normal up to the eighteen weeks, and it turned out to be a socially indicated abortus—abortus provocatus, and that was simply because the woman wanted to get rid of the fetus”. This is terrible.

While there is no certainty about the origin of HEK293, Wong claims that “in all probability the cells were obtained from the embryo of a willfully induced abortion”, rather than from a miscarriage, for two reasons: induced abortions are easier to manage and the foetus are generally healthier, as most of induced abortions happen for “social reasons”, unrelated to the medical conditions of the baby. Given that Dr. van de Eb has used induced abortions to create cell lines in other circumstances, it is highly possible that this was the case also for HEK293.

(It should also be noted the use of the term “embryonic” here is incorrect as both PER.C6 and HEK293 involved foetuses much older than 9 weeks, which is considered the last stage of the embryonic development.)

What is the connection between HEK293 or PER. C6 and the Covid-19 vaccines?

HEK293 cell lines were used in the production of the AstraZeneca/University of Oxford. The same lines were used not in the production but only in the testing of the Pfizer/BioNTech and also of the Moderna vaccines.

Johnson and Johnson/Jannsen Covid vaccines use cell lines from PER.C6.

There are other vaccines under development, but not yet in use, with no connection to abortion-derived cell lines. (See here for details https://lozierinstitute.org/cell-lines-used-for-viral-vaccine-production/)

How can we justify, from a moral point of view, benefitting from an evil dating back several decades? I have explained in more details here and here that while the production of abortion-derived cell lines for research and therapy is always gravely immoral, people who find themselves at the very end of a long chain of responsibility can morally use those vaccines when medically necessary, as the Vatican and many impeccably pro-life moral theologians have explained.

More ethical alternatives always have to be preferred, if available, however.

The public is not responsible for the grave evil that has been committed at the origin of those cell lines. The use of “tainted” vaccines does not imply condoning or ratifying their source. Nonetheless, this grave act of injustice has to be publicly denounced so that only ethical alternatives will be employed in the future.

martedì, febbraio 16, 2021

I believe I have a moral duty to take the Covid-19 vaccine

I will take the Covid-19 vaccine, when available, and I believe that most of us have a moral duty to do so. I also understand why many have reservations about its safety, its efficacy and its morality.

(I have already discussed here and here blog the morality of using vaccines using cell lines derived from abortions.)

As I am not a medical expert, I won’t address the first two issues (safety and efficacy) here and I would rather invite everyone to get informed from a variety of reliable sources.

Instead, I will address the ethical factors that need to be considered, in the hope that my thoughts will help others to make up their own mind.

We are dealing here with what moral philosophy call prudential matters, i.e. practical decisions that need to take into consideration the general rules but also the specific circumstances. As these circumstances are different, the outcome of our judgements will be different too and I am not surprised if someone will come up with a diverse conclusion, even if they agree with me in principle.

Our culture overestimates the value freedom of choice and bodily autonomy, but the current pandemic shows how much we depend on each other and it reveals to what extent my decisions - particularly with regard to vaccination - have decisive impact on others.

Our primary ethical consideration should be towards the common good. In deciding what is the right thing to do, I should take into account the good of my community, particularly of those most vulnerable and of those around me that will be directly affected by my own choices.

The success of vaccination programmes depends on widespread compliance. In other circumstances, it is the sacrifice of a few that brings benefit to the rest. Think of soldiers who give their lives to save the whole country. This case is different because vaccination protects both individuals and society, so it is beneficial to all. At the same time, my choice of taking the vaccine does not impose serious threat to others, as generally the only concerns are at individual level. Therefore, we all have an interest in been vaccinated. Do we also have a moral duty?

Yes. However, there are two group resisting this: those who think they do not need vaccination and those who believe vaccines are more harmful than beneficial for them. In both cases, they disregard the common good.

Those who believe they are less likely to be impacted by the virus are also more likely to refuse vaccination and to not comply with hygienic restrictions. They generally young and in good health.

It is not only selfish to take advantage of mass vaccination without accepting the individual costs of achieving it, but it is also irrational to be in the unprotected category. Even when the impact is minimal - “it’s no more than a flu” they say - they expose others to a serious infection.

There is no moral justification for this careless position.

Those, instead, believing that the collective benefits do not outweigh the personal risks should acknowledge the sacrifices others, healthcare professionals for instance, have made for them. Some have lost their lives to save ours.

We should think and act according to a sense of responsibility, rather than personal autonomy and individual choices. Solidarity should take priority over personal concerns.

I am convinced that those, like myself, who have no medical counterindication, have a moral duty to vaccinate. It is a duty towards vulnerable patients who cannot protect themselves, and towards those who have made significant sacrifices.

It is also ethically important to set virtuous example by publicly supporting vaccination. Vaccination needs to be a collective action to optimally effect the common good. The benefits for all will only arrive if there is a wide participation. Any legitimate concern about risks should be addressed from the point of view of the common good.

I appreciate the good faith of those who will reply that, in their knowledge, the cure is worse than the disease. This is an argument beyond the scope of my competence and so I won’t engage in medical matters. I can only say that, having considered the different perspectives, I am not convinced by those who downplay the severity of this disease or emphasise the damages, rather than the benefits, that the vaccines will cause. Their concerns are not unfounded and we need critical voices but, on the balance, I cannot honestly follow their conclusions.

I am convinced that those who object to vaccination are imposing a risk not only on themselves but also on others. Unless one has medical contraindications, the right thing to do is to vaccinate.

sabato, febbraio 13, 2021

Jacques Maritain. Il contadino della Garonna

LETTERATURA: I MAESTRI: Jacques Maritain. Il contadino della Garonna

da “La fiera letteraria”, numero 20, giovedì 18 maggio 1967

Forse il modo più efficace per non intendere il significato e l’intento della recente opera di Jacques Maritain — Le paysan de la Garonne, Desclée de Brouwer, Parigi 1966, pagg. 406 — leggerla attraverso le lenti deformanti delle polemiche che ne hanno accompagnato e seguito la comparsa. La cultura cattolica, scossa dalla incisività e dalla efficacia della diagnosi maritainiana, ha largamente reagito con apoteosi e anatemi (anche se più con anatemi che con apoteosi). Da un lato si è voluto vedere nel Contadino della Garonna colui che ha smascherato l’anticristianesimo post-conciliare — e forse anche, in parte, conciliare — richiamando la coscienza cristiana alla riproposizione delle categorie tradizionali contro ogni eversiva cessione al mondo moderno ; dall’altro vi si è scorto il difensore di superate, retrive e dogmatiche posizioni costantiniane, il reazionario che cerca invano di frenare quel clima di libertà e di impegno che la chiesa giovannea avrebbe introdotto.

Sono, questi, due atteggiamenti sterili e negativi, non consentono di cogliere in tutto il suo significato il discorso maritainiano, il quale viene politicamente classificato, con i toni della esaltazione o della condanna, come discorso-di-destra, senza tenere presente che Maritain si propone appunto di rifiutare come inadeguata proprio questa classificazione. Un attento esame degli atteggiamenti politici assunti dal Maritain mostra infatti chiaramente l’impossibilità di una attribuzione tout court di queste denominazioni politiche a un uomo che le ha sempre rifiutate e che ha assunto, di volta in volta, atteggiamenti che solo su-perficialmente potevano essere classificati di « destra » o «sinistra». (L’autore di Antimoderno non esitò a schierarsi contro il nazionalismo de l‘Action française; e tuttavia il difensore della democrazia personalista, comunitaria, teista e plurista non ha mai rinnegato la condanna del mondo moderno e ha chiaramente rifiutato il comunitarismo del Mounier.

I PIONIERI BALBUZIENTI

Maritain lo afferma decisamente: il cristiano non è di destra né di sinistra (un tema, questo, svolto con coerenza e decisione sin dalla Lettera sull’indipendenza del 1935). Destra e sinistra sono due categorie politiche: in quanto tali non riguardano l’impegno del cristiano; ma sono anche categorie psicologiche: esse indicano due temperamenti innati, che privilegiano l’essere o il dover-essere (e che, al limite, degenerano nel cinismo e nell’utopismo). Maritain ammette di essere, per temperamento, di sinistra; ma rifiuta la coincidenza tra sinistra psicologica e sinistra politica. Purtroppo coloro che tendono a inserire la problematica maritainiana in una denominazione meramente politica sono proprio quelli che sono incapaci di porsi al di sopra di queste classificazioni: i montoni e i ruminanti. I « montoni di Panurgo », tipi dell’estremismo di sinistra, sono mossi dalla cupidigia del nuovo e dell’accordo col mondo; i « ruminanti della Santa Alleanza », prototipi dell’estremismo di destra, agiscono invece sotto la spinta della prudenza e della sicurezza. Sono due pericoli costanti della coscienza cristiana, ciascuno dei quali prevale sull’altro a seconda delle diverse circostanze storiche: nella nostra epoca post-conciliare i montoni prevalgono sui ruminanti — soprattutto nelle facoltà teologiche.

La « cultura » cattolica, infatti, attraversa un periodo difficile e tormentato: i ruminanti sono quasi tutti divenuti montoni (anche i montoni, del resto, sono ruminanti!). Se, prima, le vecchie misture teologiche venivano continuamente e acriticamente riproposte senza una originalità o profondità, ora, invece, le novità più impensate e irriflesse vengono avanzate come scoperte e conquiste. In realtà, osserva Maritain, questi « pionieri » sono ritardatari e balbuzienti, in quanto solo la precedente chiusura nei confronti del mondo moderno li induce ora a una acritica apertura a miti, che il mondo moderno stesso ha ormai superati. La dialettica antinomica di sadismo e masochismo, sulla quale così opportunamente la sociologia psicoanalitica di Eric Fromm s’è soffermata, è uno schema interpretativo di prim’ordine per intendere la metamorfosi del ruminante in montone.

Il servizio reso dal Maritain alla verità cristiana in oltre cinquant’anni di attività veemente e contrastata consiste appunto in questo tentativo di mostrare che il kerygma evangelico è molto al di sopra del cibo dei ruminanti e dei montoni. Era naturale che lo sforzo del Maritain, volto dapprima prevalentemente contro i ruminanti — numerosi e potenti nel periodo preconciliare — si dirigesse ora contro i loro diversi e pur simili eredi: contro i montoni, potenti e numerosi nel periodo post-conciliare. Con sottile e incalzante ricerca Maritain discopre tutti i miti cari al neomodernismo di oggi (quel neomodernismo rispetto al quale il modernismo condannato, giusto sessant’anni fa, da Pio X era un semplice raffreddore).

In primo luogo la cronolatria: che è l’adorazione dell’effimero e del meramente temporale. Il trionfo progressivo dello storicismo nella cultura moderna e nella stessa coscienza comune induce il neomodernista a una genuflessione davanti al mondo, assunto nelle sue strutture naturali e temporali. Ciò a cui, consapevolmente o inconsapevolmente, conduce questo atteggiamento è la completa temporalizzazione del cristianesimo. Per questo il mito cronolatrico è accompagnato dal mito perfettistico, cioè dalla fede nel progresso storico e temporale dell’umanità: il carattere escatologico del messaggio cristiano viene secolarizzato e laicizzato ; il fine ultimo della storia viene posto in continuità con lo svolgimento della storia stessa e l’azione dell’uomo in essa viene considerata come cooperatrice dell’azione divina (semititanismo): « la sola cosa Che conta è la vocazione temporale del genere umano, il suo cammino contrastato ma vittorioso verso la giustizia, la pace, il benessere. Invece di comprendere che bisogna dedicarsi ai compiti temporali con una volontà tanto più ferma e ardente quanto più si sa che il genere umano non giungerà mai a liberarsi completamente del male sulla terra — a causa delle ferite di Adamo, e perché il suo fine ultimo è soprannaturale — si fa di questi fini terreni il vero fine supremo dell’umanità » (p. 88).

Alla base di questa confusione v’è la pretesa dell’autonomia del temporale. Per tutta la vita Maritain si è battuto, contro i ruminanti, per proclamare la distinzione tra temporale e spirituale: l’era sacrale o barocca è irrimediabilmente (e salutarmente!) finita e il temporale non può essere più considerato come la tutela dello spirituale. Ma distinzione non significa separazione o autonomia. E’ vero che il mondo temporale rifiuta ogni richiamo al regime sacrale, ma non è meno vero che essi debbono collaborare armonicamente e gerarchicamente (tesi espressa dal Maritain già nel 1927 col Primato dello spirituale). E’ così che, con singolare contraddizione, l’autonomia del temporale diviene, nel neomodernismo, divinizzazione di un mondo riconosciuto sconsacrato sino all’ateismo: « la distinzione tra il temporale e lo spirituale, tra le cose di Cesare e le cose di Dio, si oscura inevitabilmente nei cristiani di cui parlo. E i più decisi la negano già rigorosamente. E’ naturale: se il regno di Dio non ha realtà al di fuori del mondo, non è che un fermento nella pasta del mondo » (p. 89).

Certo Maritain comprende le intenzioni di questo processo. Esse si possono riassumere in un altro mito del nostro tempo: la demitizzazione, cioè il disperato tentativo di mantenere la fede in Cristo in un’epoca storica che ha elaborato categorie mentali sostanzialmente incompatibili con essa. Ciò che mostra la pretesa demitizzante è la buona fede dei montoni neomodernisti. Essi secolarizzano il cristianesimo per salvare il cristianesimo: « Ecco un’altra bizzarria della natura umana: con una fede tormentata, e anche il meno chiara possibile, ma con una fede sincera in Gesù Cristo, tradiscono il Vangelo a forza di volerlo servire » (p. 23).

Un altro mito, verso il quale il Maritain dirige le sue armi, è quello sociomorfico. Se v’è un carattere costante della politica del cristiano, è il riconoscimento del primato della persona sulla società. Ora il mondo moderno privilegia invece la società: l’idolo del neomodernismo è, a questo proposito, il Mounier, Con la sua celebre definizione « personalista e comunitario ». Maritain ha buon gioco non solo nel rivendicare la paternità di questa espressione, ma anche nel rivelarne la sostanziale ambiguità: « Io stesso non sono senza qualche responsabilità… Questa espressione è giusta, ma una considerazione sull’uso che ora se ne fa non mi consente di esserne fiero. Infatti, dopo aver pagato un lip service al “personalista”, è chiaro che è il ‘’comunitario” che viene prediletto » (p. 82). Tutto ciò risulta chiaro anche dalla banalizzazione neomodernista della liturgia, che confonde comune e unitario, giungendo all’errata conclusione di un contrasto tra liturgia e contemplazione (le quali, invece, reciprocamente si richiamano). Il neomodernismo, infatti, odia la contemplazione, in accordo col mito operativo del mondo moderno: si ritiene che l’impegno del cristiano debba essere riversato nelle imprese mondane e sociali; e si maschera questa parzialità inventando il mito della contemplazione come astratto intellettualismo privo di carità (mentre essa è « intelletto d’amore »).

DISGUSTO PER LA RAGIONE

Né il neomodernismo odia solo la contemplazione mistica: la sua urgenza pragmatica lo induce pure a un rifiuto della contemplazione razionale. Logofobia: ecco un altro mito neomodernistico. Il montone ha un connaturale e insuperabile disgusto per la ragione filosofica (come il ruminante, del resto): « Noi siamo convinti che non v’è che un solo tipo di sapere possibile — quello che è puro di ogni metafìsica — e, nell’ordine di questo sapere, un solo e unico tipo di conoscenza incrollabile e autenticamente capace di prova: la Scienza » (p. 167).

Alla base di queste false monete intellettuali, sulle quali è stata impiantata una redditizia industria editoriale fatta di luoghi comuni e di facili convenzioni, è l’incapacità di risolvere adeguatamente il rapporto tra verità, libertà ed efficacia. Nella civiltà moderna, infatti, i termini « libertà » ed « efficacia » hanno nettamente prevalso sul termine « verità ». Il rapporto autentico, espresso nella nota affermazione di Giovanni 8, 32 (« Et veritas liberavit vos »), è stato capovolto, con la pretesa di raggiungere una efficacia, che in realtà si rivela inefficace: « Il fatto è che ciò che non vuole che l’efficacia, e un’efficacia senza limiti, è quanto v’è di meno realmente efficace (perché la natura e la vita sono un ordine nascosto, non un puro scatenarsi di forze), mentre ciò che ha l’aria meno efficace (se è di un ordine superiore a quello delle attività legate alla materia) è ciò che possiede la maggiore reale efficacia» (p. 139).

Un’opera come Le paysan de la Garonne risulta illuminante circa i reali intendimenti, fedelmente e coerentemente perseguiti in una intera vita di ricerca, del Maritain. La lettura di quest’ultimo scritto getta luce fortissima anche sugli scritti precedenti e dissipa pericolosi equivoci. Tutto lo svolgimento che il pensiero neomodernista francese ha ritenuto di compiere partendo dalle premesse maritainiane, viene da lui indicato come frutto di un fraintendimento. Maritain Sa bene di avere indicato una strada, in tempi in cui le sue parole risultavano eversive e inaccettabili come risultano, per diversi motivi, i discorsi del contadino della Garonna, che forse non mette i piedi sul piatto, come il contadino del Danubio, ma certo « chiama le cose col loro nome » ; ma sa anche che questa strada, impervia e tortuosa, è percorribile solo da chi sia pervenuto a una accorta ed equilibrata definizione dei compiti del cristiano nel mondo. In questo senso non solo Maritain ha precorso e preparato il Concilio, ma lo ha anche continuato contro le degenerazioni anticonciliari.

Il Concilio ha indicato come imprescindibile la missione temporale del cristiano ; ma ha anche mostrato che tale missione unicamente trae senso e realismo dalla coscienza che il cristiano agisce nel mondo ma non è del mondo, dalla consapevolezza che il mondo non va solo migliorato, ma soprattutto santificato. Se il manicheismo, pel quale il mondo è, in sé e per sé, male, contrasta con la coscienza cristiana, non meno le si oppone il pelagianesimo, pel quale la sfera del mondano è autonoma e quasi divina. A questi due estremi Maritain contrappone la difficile situazione del cristiano, che agisce nel mondo pur conoscendone la provvisorietà e la finitezza, che non accetta tutto e non rifiuta tutto, che si impegna, con la salda consapevolezza della distonia qualitativa tra mondo e Regno, non a risolvere i problemi del mondo, ma ad aiutare il mondo a risolvere i suoi problemi.

Contro le semplificazioni neomoderniste Maritain rivendica la difficile, straniera e incompresa situazione del cristiano — di quello di ieri come di quello di oggi e di sempre — : « come laico è del mondo, è del secolo, e opera per questo fine che non è il fine ultimo, cioè per il buon andamento del mondo, per il bene, la bellezza e il progresso del mondo. Come membro della Chiesa opera per il fine ultimo, che è il regno di Dio pienamente compiuto e non è di questo mondo; è nel mondo senza essere del mondo » (p. 299).

E’ per questo che Maritain può affermare, senza alcun dubbio, la sua fedeltà alla Chiesa e al Concilio: le toccanti pagine iniziali dedicate a una rievocazione della grande assise della cristianità non sono né convenzionali né opportuniste. (E le due citazioni del Maritain nella recente enciclica di Paolo VI Populorum progressio confermano, dopo tante polemiche e incomprensioni, la validità di questa pretesa). Una vita totalmente spesa al servizio della verità cristiana non poteva concludersi più degnamente, in perfetta continuità con tutte le precedenti battaglie. Forse la fedeltà alla filosofia di San Tommaso — pur chiaramente distinta dalla scolastica tomista di bassa lega — non può essere accettata da tutti ; forse l’eccessiva insistenza su fatti personali ingenera talvolta qualche stanchezza ; forse la lunghezza di talune autocitazioni poteva essere evitata, con vantaggio per la snellezza del volume. E tuttavia Le paysan de la Garonne risulta illuminante e sollecitante: contro la scolastica del conformismo, che a parole esalta il dialogo e in realtà non accetta la critica (alcune astiose reazioni con cui certi rotocalchi cattolico-progressisti hanno accolto la comparsa del volume ne sono una chiara riprova) Maritain propone la criticità di un discorso integrale e realista. Tale discorso non è né mellifluo né accomodante ; anzi, è un discorso provocante e deciso, come Maritain stesso espressamente ammette: « Bisogna avere lo spirito duro e il cuore dolce » (p. 122). Maritain insiste opportunamente e inopportunamente ; il suo intento non è né la condanna, né il rifiuto, è la polemica (solo per questo egli non ha voluto avanzare alcuna critica a personam e ha quindi taciuto, con la sola eccezione di P. Schoonenberg, i nomi degli autori neomodernisti; e al Teilhard de Chardin vengono dedicate pagine serene e penetranti).

Maritain vuole, anzi, mostrare la validità e la necessità di quell’aggiornamento, che il Concilio ha proposto come imprescindibile e che coincide con la storia stessa della Chiesa ; di quell’apertura ai non-cristiani, che lo Schema Tredici ha indicato come opportuna e salutare; di quell’impegno nel mondo cui il cristiano non può sottrarsi senza cadere in un comodo ed egoistico narcisismo teologico. Ma queste valide istanze assumono un senso solo entro la tradizione della Chiesa, che il Concilio continua, non distrugge; entro quella tradizione che afferma, contro i miti storicistici e sociomorfici, il primato della contemplazione.

L’ultima parte del volume, in cui le notazioni critiche si placano e il discorso diviene preghiera, ne costituisce insieme la conclusione e il criterio: « La contemplazione è qualcosa di alato e di soprannaturale, libero della libertà dello Spirito di Dio, più bruciante del sole d’Africa e più fresco dell’acqua del torrente, più leggero della peluria dell’uccello, inafferrabile; sfugge a ogni misura umana e ogni umani nozione sconcerta, è felice di abbassare i potenti e di esaltare i piccoli, è capace di ogni travestimento, audacia, timidità ; è casta, ardita, luminosa e notturna, più dolce del miele e più arida della roccia ; crocifigge e beatifica (ma soprattutto crocifigge) ; talvolta essa è tanto più alta quanto meno si mostra » (p. 332).

Ha ragione Charles Journet: «Bisogna tacere e ringraziare ».

giovedì, febbraio 11, 2021

Medical bodies unite in opposition to assisted suicide Bill

Some of the most important medical bodies in the country have now declared to be against Ireland legalising assisted suicide. Several have sent submissions to the Oireachtas Justice Committee and expressed opposition to far-left TD Gino Kenny’s ‘Dying with Dignity’ Bill. We must hope the voices of some of the country’s most distinguished doctors will be listened to by politicians. The various medical organisations are opposed for a similar reason; they believe assisted suicide will prey on the most vulnerable patients.

What follows is a selection from their submissions.

Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

“The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) believes that the proposed legislation is not in accord with best medical practice. The introduction of doctor assisted suicide is not in the best interests of patients and does not address the real issues of death with dignity. Much better that the State would not persist in this but instead support the neglected area of palliative care which has been so beneficial but could be undermined by doctor assisted suicide. … RCSI believes that the introduction of euthanasia will have a harmful effect upon society. … RCSI believes that the risks of introducing a legal structure to allow assisted suicide as set out in this bill would do more harm than good and, on this basis, that the bill should not be progressed. It is feared that legalisation of voluntary euthanasia and physician assisted suicide would create a precedent to extend the practice to handicapped and sick individuals also, who do not suffer so much themselves, but rather are a perceived burden to society. … The consequences of the Bill are both legal medical and societal. It is at variance with the core values of the medical profession particularly in the area of patient protection. It has the potential to fundamentally damage the doctor/patient relationship.”

Irish Society of Physicians in Geriatric Medicine

“The Irish Society of Physicians in Geriatric Medicine (ISPGM), representing over 130 specialists in the care of older people, after a survey of its members wishes to give the strongest possible endorsement to the 2017 and 2020 Position Papers of the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland and submission to the Oireachtas Committee raising deep concerns about the many negative impacts of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia on the practice and ethos of care during life and for end of life care. … It is clear that not only are there intrinsic deep challenges posed by physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia but also that it can neither be restricted nor adequately regulated: in virtually every jurisdiction where it has been established it has extended to conditions – psychiatric illness, dementia, children, etc – far beyond the original proposal for restricted circumstances.”

The College of Psychiatrists of Ireland

“If enacted this Bill will result in a profound change in medical practice, affecting how doctors interact with patients who are terminally ill, but also how doctors view themselves as healers. … As psychiatrists, we are concerned that the enactment of this Bill may eventually lead to physician assisted suicide for people with mental disorders, as has occurred in in the Netherlands and Belgium. In both countries, such a request was initially excluded by the guidelines, yet this attitude has changed over time. … The College consider that it is not appropriate to legislate for physician assisted suicide of individuals with life-limiting conditions; rather legislation should be proposed to enable people to receive appropriate health care in a timely and compassionate manner so as to promote and protect their dignity. Although described below are numerous defects in the Bill as drafted, the College does not support the Bill and believes that no changes can make it acceptable.”

Irish Healthcare Professionals for Dignity in Living and Dying

“We, the undersigned, are gravely concerned by the proposal to legislate for assisted suicide and euthanasia, also described as assisted dying in Ireland. As healthcare professionals we have respect for each individual, value personal autonomy and also share an interest in protecting and advocating for people who are nearing the end of their lives and who may be vulnerable and at risk. We believe the bill creates risks for many receiving healthcare that outweigh any potential benefits. This concern is based on our collective experience over many decades of providing health care to people and their families in Ireland.” (Signed by 2,172 healthcare professionals)

Other submissions from consultants (including palliative care, gerontology, neurology and psychiatry) and from professional medical organisations (RCPI, IPMCA, RPMGNI, APMBI) are not publicly available yet but it is understood that they all oppose the Bill which is before Oireachtas Committee on Justice.

No professional or training medical body has expressed support for the Bill.

domenica, febbraio 07, 2021

sabato, febbraio 06, 2021

Assisted suicide submission sows confusion about passive euthanasia

As mentioned in the previous blog, a document in support of euthanasia and assisted suicide has been submitted the Oireachtas Committee on Justice by a small group of Irish doctors. That blog examined how the document’s reasoning illustrates the existence of a slippery slope even while denying it. This blog will look at its ambiguous and confusing use of the term “passive euthanasia”, because based on the document’s definition, it seems non-controversial, which is far from the case.

Here is how the authors of the document define passive and active euthanasia: “All forms of euthanasia involve the intention to hasten death in the patient’s interests. Passive euthanasia involves intentionally letting a patient die by withholding a treatment, such as artificial life support from a ventilator or a feeding tube. Active euthanasia involves the intention to hasten the death of a patient through an active means e.g. injection of an agent.” (p. 32)

This definition (“intentionally letting a patient die by withholding a treatment”) is correct but in the same document the authors describe a different situation and call it incorrectly “passive euthanasia” as well. They says:

“When it comes to end of life care the burden of any treatment needs to be balanced with the benefit of that treatment. In some instances, the benefit of treatment is less than the possible burden and treatment is either withheld or withdrawn. Examples of this include, stopping antibiotics or stopping intravenous fluids in frail elderly patients who are unlikely to live and who are suffering. This hastening of death by withholding treatment and allowing the illness to take its course is a form of passive euthanasia.” (p. 5)

No, it is not.

In Ireland, a treatment is withheld or withdrawn when it is considered futile and non-beneficial or on request of the patient, as no treatment can be forced. In those cases, the intention of the doctor is not to hasten or procure death and it is important to highlight this point, to avoid ambiguity and confusion.

This is not passive euthanasia, as the document incorrectly claims, because the intention of the doctor is not to let the patient die.

Death will occur naturally as an unintended and inevitable consequence. It is foreseen but not procured and the difference is critically significant, from a moral and also from a legal point of view.

This course of action is morally and legally acceptable according to the principle of the double effect. Sometimes our actions have a good and a bad effect. A surgery, for instance, is beneficial but also causes pain. When we aim at a good action (necessary surgery), the secondary bad effect (causing pain) is morally acceptable if it is not intended but also not avoidable and proportionate.

Likewise, giving a person morphine to reduce pain even if the person’s life might end a little earlier as a result, comes under the principle of double effect because the intention is to kill the pain, not the patient.

In their documents, the doctors ask: “how can active euthanasia be universally wrong while the practice of passive euthanasia has widespread support?” (p. 5)

But if passive euthanasia means, as they say, “intentionally letting a patient die by withholding a treatment”, where is the evidence that it has widespread support?

What is universally accepted is not passive euthanasia, which is killing, but the doctrine of double effect that in appropriate circumstances justifies the suspension of non-beneficial treatments.

Passive euthanasia intentionally ends a life while, instead, withholding or withdrawing futile or overly-burdensome treatment lets a life follow its natural course until the end, when medical intervention is not considered appropriate.

In the first case, the doctor kills, in the second one, illness kills. The role of the doctors is completely distinct and this is why healthcare professionals who oppose active and passive euthanasia, have no problem in stopping a treatment when it is not beneficial anymore, even if the patient will inevitably die. They are not responsible for that death as they have not caused it.

This is a fundamental distinction that the document fails to make, rendering the whole submission confused and void.

—-

Photo by Online Marketingon Unsplash

martedì, febbraio 02, 2021

Pro-euthanasia submissions show the slippery slope is real

A new group called ‘Irish Doctors supporting Medical Assistance in Dying (IDsMAiD)’ has made a submission to the Oireachtas Justice Committee that is examining Deputy Gino Kenny’s ‘Dying with Dignity Bill’. The submission denies that a slippery slope exists once you legalise the measure, while at the same time confirming its existence by opening the door to assisted suicide on wider grounds than the Kenny Bill envisages.

The document was signed by about 100 doctors, some of whom were involved in the campaign to repeal the 8th amendment. (A document opposing the Kenny Bill has been supported by 2,500 healthcare professionals.)

Having denied the existence of a slippery slope, the IDsMAiD doctors then open the door to the possibility of expanding the criteria for eligibility in the future. For instance, they are open to allowing euthanasia for patients with dementia who have made advanced requests. “With more research and experience from other jurisdictions, relating to informed consent for MAiD in patients with dementia, this is something which could be dealt with on a legislative basis in the future.” (p. 27)

On the face of it they are against allowing assisted suicide on the grounds of mental illness, but then they say: “Further research and studies are required before it should be considered.” (p. 25).

What about ‘assistance in dying’ for those with serious, but non-terminal physical illnesses or disabilities? One of the authors of the submission is Dr Brendan O’Shea, former head of the Irish College of the General Practitioners. On Twitter, The Iona Institute’s David Quinn asked him if he was open to the idea of offering euthanasia to patients with non-terminal illnesses if they have ‘unbearable suffering’. He replied: “For those with unbearable pain and non-terminal illness, we need a debate. Speaking for myself, I would like the choice.”

The term “unbearable pain” is, as the document admits, highly subjective. It could mean mental anguish rather than actual physical pain. What is “unbearable” for one person might be bearable for another.

As we know from the experience of other countries, once assisted suicide and euthanasia are introduced the grounds always expand with time. Our own submission makes this clear.

The IDsMAiD document says that “any future changes in criteria or safeguards will also require further legislation”, meaning any progression down the slippery slope would have to be passed by the Oireachtas.

But this is not necessarily the case. In other countries, more permissive interpretations of the law have been allowed by the courts or by review committees and professional bodies.

In the US, for instance, the Oregon Health Authority took an expansive interpretation of what constitutes terminal illness and new conditions were included, without change in the legislation.

It is actually difficult to avoid slipping down all the way and eventually accepting what organisations such as ‘Exit International’ wants, which is assisted suicide for anyone capable to making a ‘rational’ decision, but they do not have to be sick at all, just sick of life.

Again, the document admits that “the concept of suffering is entirely subjective and cannot be removed through medical advances from all patients” (p. 6). Once this attitude is accepted, it will be easy to extend the intentional killing of a patient to minors or to those who are unable to decide for themselves (particularly if they have signed advanced directives), or to those who suffer from non-terminal conditions. This is precisely what happened in the Netherlands and in Belgium.

Even if this document is only the expression of a minority, it is frightening to see doctors supporting the legalisation of euthanasia. They use the ambiguous expression Medical Assistance in Dying, as if patients are not assisted medically when they die in Irish hospitals or as if someone would oppose this.

The group totally supports the Kenny Bill in principle, and they recommend no further restrictions, apart from asking that any doctor participating in an act of assisted suicide should be on the specialist register of the Irish Medical Council.

More needs to be said about their document, but this can wait until my next blog.

—

Photo by Bermix Studio on Unsplash